Writing

This is a revised article that was originally published in the Summer 2003 edition of the ASIFA-Atlanta publication, Keyframes. John Musker had visited SCAD in Savannah, GA the previous November to do a presentation on Treasure Planet for the Savannah Film and Video Festival, and to meet with the students. The following article was compiled from questions and answers covered during the presentation, and the opportunity to sit down and talk with the director and supervising animator, Nancy Beiman, shortly afterward.

The ship, “R.L.S Legacy”, from the animated film Treasure Planet. Copyright Disney.

All this is fresh in his memory because he’s just come from Edinburgh where he was promoting his newest feature film, “Treasure Planet,” written and directed with longtime Disney partner Ron Clements, and attending haggis ceremonies. He’s in Savannah now, having stopped briefly in L.A. to pop in on his daughter’s Halloween party and to pick up his wife, Gail, who has kindly taken on the task of reminding him which time zone he is in. To help register his current location, he’s enjoying one of this local community’s staple dishes: fried green tomatoes, served from the kitchen looking fried and green.

Nancy Beiman and John Musker, CalArts classmates

John is in town to present at the Savannah Film and Video Festival and to meet with animation students from the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD). He shares the spotlight with one of the “Treasure Planet” artists responsible for lead animation and concept development who, to the good fortune of the Savannah film community, already lives and works here. Nancy Beiman is part of the animation faculty at SCAD, but 27 years ago she was a classmate of John’s at CalArts. Over the years they’ve had plenty of chances to work together. Nancy was supervising animator for the three Fates in Hercules, another Disney feature co-directed by John and Ron. On “Treasure Planet,” she not only designed and animated one of the pivotal characters, but also threw her meticulous attention to detail into researching some of the hybridized visual elements the film’s unique artistic direction would require.

Following Disney tradition, “Treasure Planet” uses the framework of a classic children’s book and twists and molds elements into a fresh retelling. John and Ron had this fresh idea almost two decades ago. The film’s concept was originally pitched at a Disney “gong show” — a chance for anyone working at the studio to present their idea for an animated feature to the Disney brass. Their song and dance essentially consisted of a two-page little number with a nautical theme and a backdrop as big as the universe itself. Treasure Planet was to be the science fiction version of the Robert Louis Stevenson classic, and they dubbed it “Treasure Island in Space.” But the maritime adventure was turned down along with another sea-related tale also performed by Ron and John called “The Little Mermaid”. “Treasure Island in Space” was thought to be too similar in concept to “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” which was due out the following year. Of course, Disney changed their minds about “The Little Mermaid,” and after twelve years of mulling it over (and letting a few more Star Trek movies slip by), changed their minds about “Treasure Planet” as well. Shortly after finishing “Hercules,” the two were able to dust off their treatments, scripts and storyboards, and start concept development on how to put ancient galleons and swash-buckling pirates into outer space.

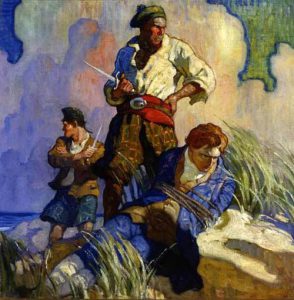

Brandywine style by artist N.C. Wyeth. Cover for the book “David Balfour”.

Although the story they were after had its science fiction angle, the directors wanted to keep the warmth and feel of the 18th century. They looked to the Brandywine illustrators—artists such as N.C. Wyeth, Howard Pyle, and Maxfield Parrish— for their loose rendering style and warm colors. But much of the warmth of these paintings was achieved through the nature of the medium: oil paint. So one of the art directors, Ian Gooding, created a sample background in oil to see if the Brandywine style could be reproduced. The result was stunning, but the directors found themselves watching paint dry and recalculating what this traditional method was going to do to their schedule. They realized they would need to find a way to duplicate the style and warmth in the digital realm, typically considered too stark, stiff and cold to pull off such a feat. But where there’s a will, there’s usually proprietary software.

The software engineers who designed Deep Canvas so Tarzan could surf around the treetops needed to take things one step further. Although the software allowed artists to paint a 2D brush stroke in 3D space, the canvas was still shot-based. John and Ron wanted a looser camera, with the ability to move into the painted backgrounds while maintaining the painterly style. The illusion of the brushstrokes had to be successful from any arbitrary view, and the engineers set to work on giving the directors their dimensional oil paintings.

To combine the Brandywine-style surroundings with futuristic elements, John and Ron drew inspiration from Terry Gilliam (Brazil, Time Bandits), a director who has built imaginative worlds from anachronistic soups of past and future. At the same time, they did not want to inherit the physical limitations imposed by combining the two in outer space. Specifically, they didn’t want the reality of having to explain how one could breathe freely on the open deck of a ship while sailing through the cosmos, or worry whether the fantastical space storm they had planned was scientifically plausible. The directors agreed on a parallel universe that followed their own rules and that combined old with new at a 70/30 ratio.

Lady Washington

For the futuristic world, in many ways the sky was the limit, but to keep the visuals grounded in Robert Louis Stevenson’s world, the directors and artists had to step back in time. The artists got into as much of the 18th century world as they could, which sometimes meant trekking to museums to draw 18th century gizmos. In Nancy’s case, this meant heading to the open seas and into an actual pirate ship. Long Beach, CA is home to three replica ships that perform mock battles in the harbor including the “Lady Washington”, a Seattle merchant vessel, and a sloop, typical of the smaller faster ships pirates would have used to attack the former. True to her meticulous nature, she sailed on all three, taking pictures of the battle and experiencing one slice of sea-faring life – namely, to be shot at (gun powder only). She then convinced the directors to host a field trip aboard the Lady Washington where the temporary “crew” literally learned the ropes, walked the planking, and braved the high seas. Apparently a hurricane had recently swept through the Long Beach area and the ocean was a roiling roller coaster of mud, providing twenty foot swells and a boat ride that surpassed anything currently offered at Disneyland.

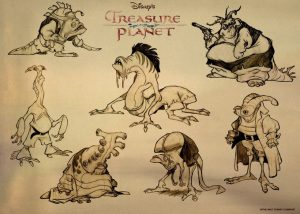

Some the crew of the R.L.S. Legacy

The 70/30 rule applied to the characters as well, but maintaining 70% of a pirate’s personality proved challenging for the PG-rated film. The animators were not allowed to show pirates smoking or drinking, two things they’re notorious for doing. Unruly behavior had to simply be a part of their personage and not due to the improper use of alcohol. But two predominantly pirate-like attributes stayed in the film: swash-buckling and being killed off in sword fights. As it turned out, what increasingly marked a pirate’s demise was not so much being in front of the wrong sword at the wrong time, but rather being too hard to draw. The character designers relished the freedom they wielded in coming up with fantastical creatures to populate the crew, but in turn, created some challenging designs with which the animators had to work. Animation is expensive, so in the case of the pirate crew, the budget spelled death, and characters were killed off in order of design complexity.

One of the most complicated character designs was that of John Silver, a kind of cyborg adaptation of the original pirate Long John Silver, sporting a mechanical eye and a dentist’s version of a swiss army knife for a right arm. John Musker joked that this was the first 5D character ever created, a combo of 2D and 3D. Glen Keane was cast as the supervising animator but essentially only covered the parts that were flesh and blood. He worked very closely with Eric Daniels who was cast as all the mechanical anatomy: specifically the arm, leg and eye. Registering the 2D and 3D elements was a big concern. Matching up the arm was not as difficult but the eye had a tendency to float around in the head if not properly registered. Glen’s reference drawings were followed closely to ensure a perfect match up. (Glen is currently trying to develop a software that will enable him to ‘keep drawing and transfer his animation to a CGI character’ without the use of conventional CGI controls.)

Jim Hawkins and Ben the Robot

Treasure Planet offered another first for Disney: a 100% CG-generated personality character in Ben the robot , voiced by Martin Short. In this case, matching the 2D to 3D was not on one character body but between two, that of Jim Hawkins and Ben. The animators decided that the best way to approach the interaction was to give lead animation to whichever character dominated the scene. The animation was especially difficult in the scene where Ben keeps attaching himself to Jim (based, by the way, on a routine called “This is Your Life” performed by Sid Caesar on “Your Show of Shows”; “Uncle Goofy” was screened repeatedly for Ben’s animator Oscar Urrezabizkaia, who is Spanish and had never heard of Sid Caesar). With the two characters interacting so closely, the directors wanted the robot character to be as rubbery as possible. The 3D folks built a special skeleton that allowed for a considerable amount of squash and stretch. For those interested in even more nitty gritty details: the robot character was animated at 24 fps, just like the rest of the movie, and even had some sequences animated on 2′s.

Billy Bones

Equally complicated was the design and animation for Billy Bones, a briefly seen but pivotal character in the story. Nancy created a spectacularly realistic lizard/dinosaur body that waddles and limps underneath the heavy cloak. The head is a kind of turtle and snake hybrid, contrasted well by the “High Cocked Hat” she chose to offset the flatness. The tricorne shape of the hat was difficult to draw and Nancy tracked down a real one that sat on a model head during production so she could turn it any way necessary. Likewise, animator Dan Hofstedt made a maquette of his character, Mr. Arrow, and sculpted his own version of the tricorne as reference.

During the presentation at the festival, Nancy proudly sported the aforementioned tricorne while she and John posed for pictures for the local Savannah paper. The two made a special point of focusing on character and element design during their talk. Students from her class spent the morning having their own character designs and maquettes critiqued by the director. The reel John brought from Scotland was complemented by footage sent especially by Disney showing some of the rough Billy Bones sequences Nancy had drawn. Not all of the footage that Nancy animated made it into the film, but she was told it would appear in the DVD version. A final first for this feature: Treasure Planet is the first Disney DVD to have been planned before the film’s release.

Special thanks to Nancy Beiman for additional notes and anecdotes.